The Torchbearer Chronicles – Claire Edelman

The most important result of a Camp Tecumseh experience is the hardest to detect. In the routine of daily life it’s invisible, even to those affected. It’s a slow burn, gentle and unwavering amidst the fury and roar of reality. Unlike the flash-bang jolts of excitement and purpose that often accompany a camp experience, this doesn’t fade as we fall back into old habits in the normalcy of home life. As every good mariner knows, a course correction of even a single degree on a long enough journey can result in brand new destinations. This is the beauty of the Tecumseh experience. It alters trajectories; quietly and assumingly, and only by minutes and degrees, but in the long game that’s all it takes. Like the frog heating up in the pot, we can’t detect the difference while we undergo change. Only later can we look back and discover how far we’ve come.

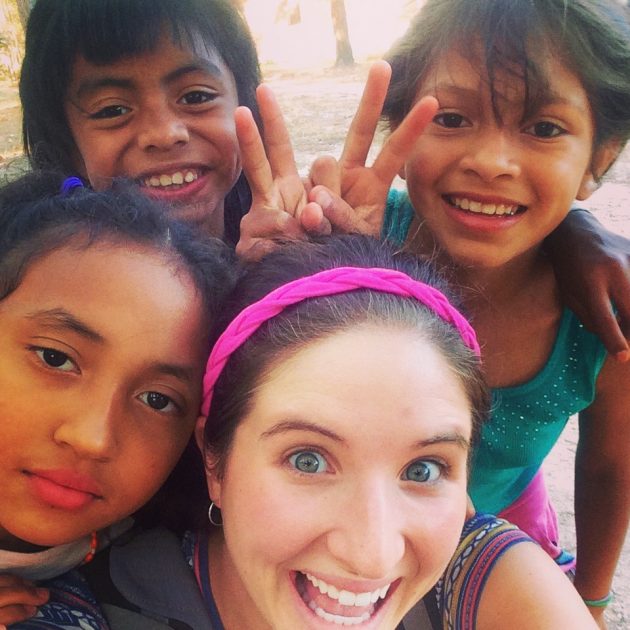

For Claire Edelman, this subtle change in trajectory has transformed a #blessed life into a blessing. From a loving family and supportive community, Claire possesses a herculean work-ethic and natural God-given ability. Now a medical school student at Duke, she’s eschewed the resume race and subsequent self-aggrandizement and blazed a path forged in the values she learned at camp: faith, love, and service. In few areas has this been more notable than her yearlong stint in Honduras, working with orphaned and vulnerable children with Nuestros Pequeños Hermanos™ (NPH),

It’s 3 o’clock on a Wednesday. Claire Edelman waits on the porch of Shoshone cabin dressed in black. Sunglasses cover her eyes. She talks into an earpiece and checks her clipboard as we approach. We’re late.

In a flurry of raised voices and guiding hands, campers rush Maddie Bien, the Lake Village assistant director, and I through the cabin and into the bathroom. A camper wielding eyeliner and blush eyes me impatiently. An array of tools assault my cheeks, lips, and eyes. “Hurry up! Hurry Up!” I hear girls yelling in the background. A fluffly white veil is bobby pinned to my hair and I’m shoved out of the bathroom and immediately blinded by camera flash. A row of girls in costume box decor processes down a decorated aisle, taking their place under the window covered in colored tissue paper. Pink and white streamers, white paper bells, and balloons transform the wood paneled cabin into a marriage chapel straight from the Vegas strip. A mustached camper grabs my elbow as Pachelbel’s Canon in D fires from a nearby iPod. At the end of the aisle, Maddie, donning a dollar store mustache and pipe cleaner boutonniere waits to take my hand in marriage.

Brief ceremony concluding, we A-frame hug to make it official before rushing outside to our reception. A cupcake cutting and smash concludes with a cacophony of clinking cans, a “just married” construction paper sign, and two makeshift airline tickets to Fiji where our happily ever after awaits. The girls run back into the cabin and slam the door. Maddie and I stare at each other in dumbfounded silence before succumbing to the gleeful grins of kids that just rode the worlds’ best roller coaster for the first time. Uproarious cheers erupt from the cabin’s open window as the ladies of Shoshone celebrate their performance. The door opens and Claire emerges, eyes gleaming, understanding that she has just become legend in the fabled pages of Wacky Wednesday.

This is Claire Edelman at her best: the wizard behind the curtain. A torrent of logistical mastery, her brilliant manipulation of details is matched only by her inexhaustible creativity. Through meticulous planning, ceaseless encouragement, and an acute awareness of others, she’s built to lead others and opportunity hunts her accordingly. If that isn’t enough, she’ll never take credit for any of it.

The Claires of the world are rare. Able, empathetic, brilliant, articulate, loving, humble, Claire’s resume is as impressive as anyone you’re likely to meet. She’s attended Washington University in St. Louis and a earned a spot in Duke’s prestigious and highly competitive medical school. She’s led brigades to Hondurus, captained state championship sports teams, served food to the homeless in soup kitchens, and counseled college sophomores through depression. By all counts she’s the child every parent dreams about.

Growing up in Zionsville, Indiana, Claire had the ideal childhood. “It was easy. I was always supported and pushed. The best things my parents taught me were to not be afraid to try new things. To not be afraid of being a beginner.” It’s a philosophy that served her well as she navigated high school work and extra-curriculars. It turned her on to Lacrosse after an injury knocked her out of Volleyball and Basketball. It led her to try Spanish and ultimately whisked her away to Honduras.

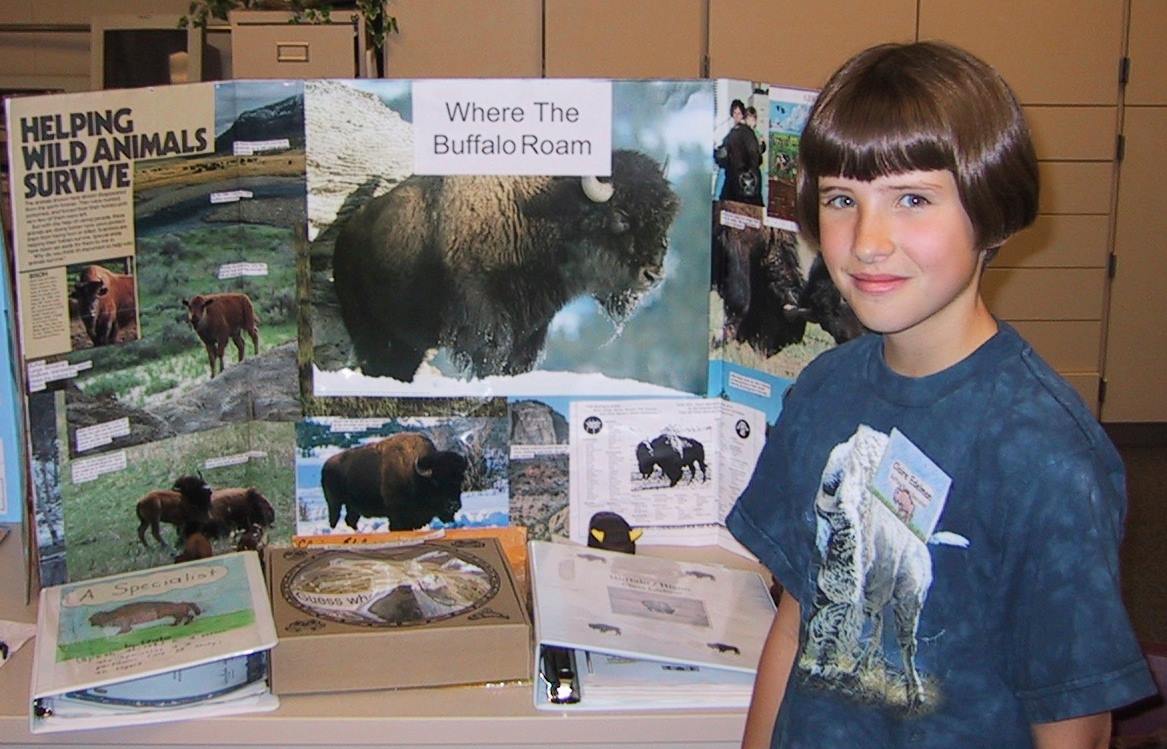

Camp Tecumseh played an essential role in Claire’s development. Her camp career began as an eight year old buck and continued every summer she could attend, even attending Outdoor Education in 4th grade. Her mom even attended as a chaperone. As a camper she always wanted to stand out. “I remember dressing up for everything. I would plan weeks in advance what I was going to wear for the theme dinner and campfire. I was always the only girl in Archery and Riflery and I really liked that.”

Over the years, a mixture of camp’s values, her mother’s example, and her growing faith instilled in her the importance of service. “That’s what I learned at camp from day one. You go out of your way to help those around you. My mom does this all the time. She is always doing stuff for others. I learned that you get more out of it than you actually put in. In the relationships that develop as a result, I feel like I come away benefiting.”

Throughout college at Washington University in St. Louis, Claire’s heart for service translated into positions that let her give back. She served as an RA, traveled to Honduras to help provide access to clean water, and spent two summers at Camp Tecumseh as a counselor and village director. A pre-med student, Claire had known that medical school was the next step in her goal to become a doctor, but she had other plans in the short term. She wanted to take a gap year after graduating, despite opposition from her parents and academic advisors. That gap year would give her the opportunity to give back. “I knew I didn’t want to go right into medical school. I wanted to come back to camp for another summer. I wanted to gain additional experience, take a break from school, and use my Spanish. My parents would always joke that my gap year would turn into my gap decade.”

After graduating from college in December, the search for gap year opportunities intensified. Working at Casa de Salude, a healthcare provider for the uninsured and underinsured in downtown St. Louis, a colleague introduced her to NPH. “I was mostly looking stateside, then I met Kate. She was an NPH volunteer in Honduras and if it weren’t for her I wouldn’t have gone. She told me NPH was like camp, but in Spanish.” Claire had traveled to Honduras twice during her undergrad years working with Global Brigades where she helped provide access to drinking water. “I knew I liked it. I liked the people and I liked the culture.” For this eager servant, medical school applications, a semester as an RA, and a summer at Tecumseh were the last remaining items on the agenda before her gap year began.

In 1954, Father William Wasson refused to press charges against a little boy who stole from the church poor box. Instead, he asked for custody of the child. A week later, the judge sent him eight more homeless boys. By the end of the year, 32 boys were in residence and Nuestros Pequeños Hermanos™ (NPH), spanish for “Our Little Brothers and Sisters,” was born. With homes in eight countries throughout Central America, over 20,000 children have grown up in the NPH family. Currently NPH cares for 3,300 children. At its core, NPH provides a loving, stable, secure family environment for vulnerable and orphaned children living in Central America. The kids of NPH are fed, clothed, housed, and receive quality education and healthcare. The program is funded by donors around the world who support the children in attendance.

In Honduras, the NPH facility, Rancho Sante Fe, is affectionately known as “The Ranch.” 2,000 sprawling mountain acres buffer the children from the abject poverty just 45 minutes north in the capital city of Tegucigalpa. The local towns harken back to the late 17th century; ox carts on dirt roads, free-range chickens roaming the marketplace, mudbrick buildings, open-air storefronts. “The main thing you see is trash and litter. There is a big dump in town and it smells terrible, but that’s their work. They crawl through the dump to pick things out they can sell. They buy food from little store fronts that sell chips and soda. That’s what they can buy, cheap stuff.” 50% of the Honduran population lives below the poverty line and almost 30% of adults are unemployed.

The children on the ranch come from all over Honduras. “We have a lot of orphans who have nobody else outside the ranch. We also have a lot who have family, siblings, aunts, grandparents, or even parents that just can’t support them. For some kids it’s a boarding school. For other’s it’s the only home they have.” In order to qualify, children must be poor and their mother must either be deceased or have abandoned them. In addition the child’s father and other family members must be unable to care for them

The facility is divided by gender, with the boys on one side and the girls on the other. The church acts the ranch’s center point. NPH groups children by age and maturity into homes known as “hogars.” Students are educated in montessori, primary, and junior high schools and every student participates in vocational training before they graduate in skills ranging from carpentry and welding to tailoring and sewing. In the library hangs a wall of fame. Its pictures include previous NPH kids who graduated from college. Next to those pictures are empty frames. “It’s used as a motivational tool. Kids want their picture in the library. Really, the whole point of NPH is to provide you with training on how to be a good person so you can go out in the world, have a family, support your family, and help end the cycle of poverty.”

A strong culture of giving back pervades the Ranch. After children graduate high school, they participate in a service year at the ranch. “This is how they give back. Most work as a “tia” or “tio” where they work directly with the kids. Others work on the farm or the garden, and others perform tasks needed by the ranch.” Even after the service year, many kids who spent their childhood at the Ranch come back in some capacity. Doctors, nurses, engineers, and tradesman all contribute their skills in addition to mentoring the kids. “Two brothers who were part of the first generation of NPH children are still here. One is an engineer. He helped design the surgery center and does whatever the ranch needs. The other brother is an orthopedic surgeon. He’s the full time doctor there and he runs the surgery center. All the people who grew up on the ranch mentor the current kids. It’s really cool.”

It’s up to the children to perform many of the essential functions of the ranch. Younger children sweep or pick up trash, while older kids work in the gardens, do laundry, and help with the younger children. For the kids, the day starts at 5am when they prepare for the day, eat breakfast, and do their morning chores. “They are so good at doing their chores. They start them young. The ranch is always so clean.”

As a volunteer, Claire had been offered two jobs. Furnished with a hotel of sorts, NPH had recruited Claire to work with guests as the visitor coordinator. She was the tour guide and hostess of the ranch. “Basically I was the translator, making sure they weren’t disrupting normal ranch life but adding to it.” Arranging travel, Claire spent much of her time traveling to and from the airport, picking up sponsors, medical brigades, and officials. As the main point of contact for visitors, Claire did her best to temper expectations. “I never want to own a hotel, it’s so hard. I’d constantly have to remind visitors that we were in the middle of nowhere Honduras. We didn’t have a lot of hot water. We didn’t have all the amenities Americans were used to.”

In addition to her job as the visitor coordinator, she also worked with women empowerment groups in the local community where she would lead discussions on topics ranging from trust to self-confidence. As one of the only volunteers allowed to leave the ranch regularly, she got to see the real Honduras regularly. “It was eye opening to see where my kids were coming from. I took my mom into town with me when she came to visit and she was shocked. She told me to never leave the ranch!”

On occasion, when medical brigades would come into town, Claire would find herself helping out in the surgery center, putting her medical background to work. “They would let me scrub in and occasionally put in a few stitches. It was a good experience, but I think I realized surgery isn’t for me.”

While her official responsibilities kept her busy most of the day, the real work happened in the evenings when she could hang out with the kids. “From 6pm to 8:30pm on weeknights and every other weekend, we’d hang out with the girls. We’d eat dinner, read books, watch movies, and do a lot of zumba. I repeated the rosary about a million times. I don’t know it in English, but I sure know it in Spanish.”

Claire’s group of girls ranged in age from 9-12, and even though she worked most closely with them, she knew everyone on the ranch. All of the girls have a different story. Some are incredibly open, sharing every detail of their young lives, while others were more reserved. It’s the job of one of the directors to know all the kids and all their stories, and when necessary would share them with the volunteers. “Sometimes he would come up, drop a bomb on you, and then walk away. One of my girls, a quiet girl who eventually warmed up, was selling crack on street corners. She had no idea what she was doing. She was just doing what her parents told her. ”

While the kids of the ranch have primary care givers during the day (the tias and tios), the job of the volunteers is to make the children feel loved. “My job was to be there and to be present. I can’t take away their bad experiences. I can’t fix their past. I can’t solve all their problems. But I can love them. I can be with them. I know how to do that. I can’t fix them. I don’t have the skills or resources, but I can love them, and that’s good enough.”

While Claire’s Spanish is exceptional to American ears, the language barrier emphasized other aspects of relationship building. “I couldn’t just form relationships out of communication. It had to be through acts of kindness and time spent with them. My language skills were fine, but it’s just not the same in a second language.” As a result, Claire’s mannerisms and activities became the focal point for her relationship with her girls. She organized fashion shows, dance offs, plays, and competitions. The girls called Claire “La Loco” or “the crazy one.” “I wanted to be fun all the time. In Honduran culture, girls are shy. They would be shy for their performances and in front of others. I wanted them to be more animated and push them out of their comfort zone. They made fun of me a lot for being so excited, but they learned that it’s okay to be different as a result.”

Claire’s favorite time of the week was Mass. Every Saturday or Sunday (the day varied depending on the ranch’s schedule), the girls and boys would join at the church. It’s the only time the entire ranch is together. “It’s such a great time to be with God and be with the girls. The best part of Mass was always the sharing of peace. I was always hug attacked by everyone around me. I couldn’t move, breathe and it was just awesome. I miss that.” Father Ronaldo served as the ranch’s priest. “He was amazing. His porch was the best place on the ranch. All the volunteers would come over and just chill. He’d come to town with us; we’d go diving together. He was really involved.”

Like our summer camp counselors at Tecumseh, the volunteers grow incredibly close during their experience. “There were 18 volunteers and six of them were from the states.” Each volunteer serves a period of 13 months with a new group arriving every 6 months. A green picnic table served as the focal point. “We’d all gather around it on the weekends or whenever and just have these amazing conversations around the table.” In the evenings, after the kids went to bed the volunteers would set up a projector and hang a sheet on the roof and watch bootleg DVDs of popular movies they had picked up from street vendors. “It’s a support network. They are the only ones who really understand what we are going through.”

When the year is up for volunteers, it’s traditional for them to make a speech at their last Mass. Claire, always wanting to stand out, deviated from the traditional of sentiment. “I wrote a poem in Spanish that was kind of funny and played up the fact that I’m a crybaby. I made a big scene to give the girls something to laugh about.” When you spend a year investing in people, it shows. On Claire’s birthday, at her last meeting with the women’s empowerment group before returning to the states, the girls had a surprise for her. “We get up to the building and I see the door is closed. When I open it, there is confetti, decorations, a huge poster with my face on it, and inspirational quotes all over the walls. It was the most detailed surprise party. There were activities and games, and 2 choreographed dances with costumes, a bunch of food, and cake. They had gone out of their way to put this whole thing on. They got all the resources themselves, choreographed the dances themselves. They got up and said nice things about me. It was the sweetest thing.”

As Claire invested in the kids of NPH, the process for admissions to medical school rolled on. Most schools require in person interviews, a difficult prospect for a candidate volunteering in a developing country. “Getting back for interviews was the hardest part, but when I did go, it was all I talked about, and all they really cared about.” Her advisors had been adamant in their insistence that she not go abroad, but her NPH experience had proved to be an asset, even if it did mean interviewing with head lice. “We all had it at some point, that’s just how it goes.”

On her way back from dropping off a medical brigade, she and some fellow volunteers stopped in Tegucigalpa to hang out for the day. “We were hiking up to the world’s largest statue of Jesus, one even bigger than the one in Rio, and I stepped away for a minute to take a picture of the view. I had a message from my mom that read, ‘you got in.’” She had been accepted to Duke. “I was freaking out, all the volunteers were making a scene with me and all these local Hondurans were looking at us like, ‘what are these gringas doing?’ There I was, under the arms of the world’s biggest Jesus, celebrating that I got into med school.”

As the Honduran dust settles, a new adventure awaits. Claire is on the primary care track in her first year of medical school. She already knows everyone in her class and has been elected to the class council. She was a starting wide receiver for her class flag football team and, in Duke tradition, camped out for basketball tickets. “It’s funny talking to my classmates, they have all done amazing things. For me, this year is about meeting those people, finding a support group, and making some time for fun. I keep reminding myself that it’s pass/fail.”

It’s an unlikely comment from a driven first year medical student at a top tier program in a highly competitive system, but it’s a comment reflective of someone who knows from experience the value of investing in other people, and taking care of yourself. “When I’m helping other people I’m happy, and excited, and having fun. It makes you feel good. It almost sounds selfish, but I do things for others because it makes me feel good.”

Claire is returning to Honduras in December to visit NPH. Over break, she’ll spend a week at home, and a week at the ranch with the kids and volunteers. She stays in contact with her girls and volunteers over social media. “They tell me not to be one of those volunteers who say they will be back, but doen’t visit for another ten years.”

Charting a sea change gets easier the further out you are, when the difference between wildly divergent outcomes can be measured in one or two degrees. In the moment, we never know what impact a Tecumseh experience will have on a camper. It plays out over decades. However, as Claire’s story demonstrates, as do countless others, these small calibrations in the hearts and minds of our youth bend the trajectory of their lives towards love, faith, and service.

This story was first published in the Fall of 2015.