“What do you want to be when you grow up?” Kids always have an answer, even if it changes daily; firefighter, astronaut, teacher, doctor, rockstar, President of the United States. Interestingly, it’s usually an occupation. I suppose that’s why John Lennon’s mythical and appropriately cheeky, “happy” answer still finds so much love on Pinterest and Instagram. For kids, there is no immediate danger in changing one’s mind. Nothing is lost if a 5 year old wants to be a veterinarian today and a monster truck driver tomorrow. As we get older, at what point do our flexible occupational imaginings transform into steadfast resolve unbent by changing circumstances and varying probabilities and ossified by the weight of expectation, competition, and ego? In a world with too much to do and too little time, our furious pursuit of professional desires becomes all-consuming. When is enough enough? To discover who we are and what we want. Sometimes we need to slow down, relax, and connect with the world around us.

“Let it change you. Let it transform you.” In university gymnasiums and auditoriums across the country, that’s the message Brit Davis delivers to throngs of exhausted, emotional college students. They’ve been on their feet for hours as they stare into the long night. This gauntlet isn’t some Greek hazing experiment for new pledges. It’s Dance Marathon, one of the fastest growing, most successful grassroots fundraising efforts in the nation. And it’s run entirely by college students.

Brit understands the transformation. It’s the same one that shuffled her plans, reset her priorities, and upended her worldview. Just a few years ago she was running herself ragged to become America’s next great anchorwoman. Today she’s one of five national managers for the Children’s Miracle Network of Hospitals helping college groups across the country raise money to support sick children and their families.

The values of service, community, giving, and relationships aren’t learned at breakneck speeds in hypercompetitive environments. They’re learned in the present. They’re learned when we take a break and pay attention to those around us. They’re learned when we allow ourselves to take a breath and experience our humanity.

IT STARTS AT CAMP

A Foundation in Faith

Brit’s first venture to camp came in 2002. As a 5th grader, she loaded on a bus and made the 60 mile journey north with her classmates from Zionsville Middle School to take part in Camp Tecumseh’s Pioneer Heritage program. “I remember staying the night. It was the middle of winter and we were all freezing, but we still had a blast. I also distinctly remember crossing the suspension bridge. The boys tried to scare all the girls by shaking the bridge as we crossed. They got in trouble.”

After the field trip, and at the urging of her friends, Brit signed up for a week of resident camp, a challenging prospect for a shy girl who had difficulty making friends. “My first year I was on a waitlist. I didn’t realize I was coming until a few weeks before. I was thrilled. I was terrified. I think most first years feel that way. Growing up I was really shy. You wouldn’t think that now, but I was really shy. Making friends wasn’t something that was easy for me as a kid. That first night, back when everything was still in River Village, we were eating the first meal. It was turkey, mashed potatoes, and biscuits. I wasn’t eating. I had been split up from my friends and I didn’t know anybody. My counselor asked what was wrong and I told her I didn’t feel well. I was tremendously homesick, but that’s the answer everyone gives. My counselor sent me to the nightingale where I hung out with the nurse for an hour. She gave me popsicles and we just talked. After that I was magically better. I went on to have the best week ever. When I came back as a counselor and my 15 year olds would get home sick I would always tell them to go have a popsicle with the nurse, we’ll be here waiting for you.”

Brit returned every summer as a camper and later joined staff. In the beginning, camp was more of a social experience, but as she grew older, camp became the foundation for her relationship with God. “Growing up my Mom was very Christian, but my dad wasn’t religious. On Sundays it was my decision to go to church. I went on some Sundays and slept in on others. As a result camp became the center of my faith.” It didn’t happen overnight. It was the culmination of moments and expressions that led to a deep, spiritual connection. “The most impactful moments for me were in Chapel when everybody was singing together, especially by year three or four when I knew all the words by heart. When you’re in that space with so many other people collectively worshipping and praising that’s where your heart starts to soften to the idea of it all.” If chapel is where Brit’s heart was softened, it was in devotions where faith took root. “I vividly remember being 13 at camp. Caitlyn Scales was my counselor and we did a feet washing devotion. That devotion was the turning point for me. It was the most powerful moment of development in my relationship with God. The simple act of cleaning the feet of the girl who slept in the bunk above me was something that was incomprehensible to me at that time. I can’t even explain it. I just get so emotional thinking about that moment. Caitlyn Scales knows that. I told her she changed my life because of one devotion. Later, I was a CILT and we did a devotion under the stars. We heard all the facts and figures about how big the universe is and how little we are in comparison. But despite the vastness of the Universe, God has created us exactly how we are, he knows us by name.”

Counselors played the biggest role in Brit’s development. “They changed my life forever because of their ability to communicate with a 13 year old girl. That’s what’s so special about them. They have an ability to understand and relate to kids when parents and adults seem like they are so far away at that point in a child’s life. That counselor interaction is what really impacted my life.”

IT’S NOT ALWAYS SUNNY IN LOS ANGELES

The downside of aspiration

At school, the thoughtful, tender-hearted girl was swallowed by the monster of professional expectation. A type-A go getter, Brit was doing everything in her power to set herself up for a career in broadcast journalism. “I wanted to be Katie Couric. At first I got involved in anything I could get into. I was president of student council, editor of the yearbook. I was in charge of everything.”

Her dedication was rewarded with admittance to the prestigious Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Southern California. A programmatic powerhouse, USC’s roster of alumni includes some of the biggest names in cinema, television, and print. Abounding in opportunities and connections for students and graduates, its success can be attributed partly to its location in downtown Los Angeles. If there was ever a chance to get her foot in the door in one of America’s most competitive industries, this was it.

USC was supposed to be a new start, an opportunity to leave Indiana behind, explore new places and broaden horizons. For a girl who had it all figured out, this move represented the next logical step. But it didn’t work. “I hated it. I couldn’t find the relationships that are so important when you’re 18 years old and trying to find yourself. I didn’t have anyone to push me, challenge me, and be there for me. I was so far from the comfort of friends and family that I had to figure it all out on my own.”

Brit’s high school quest to achieve her professional goals was all-consuming, and her tunnel-vision came at a cost. “I never took the time to be a kid. I thought I knew who I was, and who I wanted to be, when I never gave myself the time to figure out who that was. It was devastating to have put all my eggs in this basket and to have it all crumble beneath me. I had given everything I had and it wasn’t the answer. The channel wasn’t the right channel. Because I had put so much into this pursuit I questioned everything else as a result. If this isn’t the right school, is this even the right dream?”

COMING HOME

Ending up where you’re supposed to be

Brit made it through her freshman year at USC and set up a summer internship at a major media company in LA. In a serendipitous moment, Brit reached out to her parents for help. “My mom asked what I needed to do to feel like me again. The answer was pretty simple. I needed to come back to camp. I needed to come home.”

Most staff positions, particularly female staff positions fill quickly. It’s competitive, and only the best candidates become Tecumseh staff members. “I called Scott Brosman and said, ‘Hey Scott, it’s April and summer camp starts in a month and a half. I haven’t applied, gone through the process, or interviewed. I just feel this incredibly strong calling that I need to come home, that I need to be at camp. I just had this otherworldly feeling that camp was exactly where I was supposed to be.”

There were no openings. Brit was placed on a list of potential candidates to interview should the need arise to hire more counselors in the event someone backed out. Two days later, that’s exactly what happened. “I got a phone call from Scott asking if I would be willing to interview for the position. I got the job. I was coming home.”

THE CALIBRATION OF SERVANT HEARTS

Finding purpose at Camp

Arriving at staff training that summer brought the same flood of doubt and uncertainty most new campers bring with them when they first come to camp. “When I first got there I was so nervous. I had the same sinking feeling I had as a camper and the same doubts and questions. I thought to myself ‘I’ve been given such a huge amount of responsibility. I’m responsible for the lives of these children while they are here. I know how big an impact camp had on me. Now I have to provide that same experience.’ I was terrified I would mess it up. I wanted to provide that experience for my campers that they needed, while knowing my heart needed to be mended to make that happen.”

Fortunately, staff training provided the essential heart mending necessary to provide the signature Tecumseh experience. “I was immediately surrounded by people that made me feel that it is completely okay to be the people we are. LA is the complete opposite of that. I was accepted immediately for who I am. That feeling doesn’t change. It doesn’t change when you’re 8 and coming to camp for the first time, or 25 and coming back to visit a closing campfire as staff alumni. There was an overwhelming sense of relief to be here because I was loved.”

As a counselor, Brit thrived working with 15 year old girls in Seminole cabin. “I could be completely real with them. I didn’t have to dumb anything down. Sure, high schoolers are going through things on a different scale than adults, but it’s still the same struggle. How Do I fit in? Why does God love me? How can I give back? What does it take to be a good friend? At the same time I was learning more about faith. I grew in faith in those 10 weeks more than I’ve ever grown. This place lends itself to create great counselors because its so relational. I wouldn’t have had the same experience it if wasn’t for the counselors surrounding me. Every week, every day we are doing something different, knowing we are making an impact in someone’s life. They are memories we’ll never forget. I was nervous about living at camp for an entire summer before I arrived. The second I got to camp I knew I didn’t need to worry. Camp became such a home. I wish I could spend every summer there as a counselor. I still wish that.”

That summer at camp proved to be the necessary deep breath, the clarifying moment when the crossroads seem less perilous, and a decision seems possible. Brit had a close group of friends, reconnected with her family, and met a boy, Brian Vanneman.

FTK – FOR THE KIDS

The impact of Dance Marathon

At the end of the summer Brit transferred from USC to Purdue. “It was still a transition. I was going into a new place as a new person. I had a solid core of friends who were co-counselors with me who made that transition easier. They told me to get involved and they pushed me to try Dance Marathon. That encouragement ultimately became the defining factor of my time at Purdue.”

For Brit, Dance Marathon was just what the doctor ordered. “When I arrived at the call out meeting, everyone was wearing tie-dye t-shirts and tutus and dancing around the room. It was a room full of camp counselors and it was beautiful. I didn’t think I would find the perfect extra-curricular activity for counselors.”

For those unfamiliar, Dance Marathon is an on-campus student run organization that supports the Children’s Miracle Network, a group of non-profit hospitals that provides total family care for children with serious medical conditions regardless of a family’s ability to pay. Each chapter of Dance Marathon is locally supported and locally run, with all proceeds benefiting local hospitals. Purdue and IU, for example, raise money for Riley Children’s Hospital in Indianapolis. Varying in size and scope across the country, each Dance Marathon is led by a team of students to raise funds and provide mentorship and community for affected families. The Dance Marathon Event is the culmination of a year’s worth of fundraising. It’s the final hurrah in which college students, who have raised money to earn their place, stay up on their feet for anywhere from 12-42 hours at time to show their support for the hospitals and the families they serve. It’s at this event where the fundraising total for the year is revealed.

Reflective of her camp experience, Brit’s involvement in Dance Marathon started for largely social reasons. “I knew I was doing it for a good cause, but it seemed like a good place to find a group of friends at Purdue.” Brit served with some of the counselors from that summer, including Brian whom she’d started dating. Brit started on the morale committee, a group of people responsible for making sure everyone at the event is comfortable, having fun, and connected in some way. “We were the fun police. After seven hours of standing it starts to hurt. It was our responsibility to make sure people were having a good time.”

It wasn’t until the event where things clicked. That’s the case for most of the attendees. “That’s where you meet the families, and hear the stories. That’s where you get to see where the money you’re working to raise is going. At that stage I truly realized that it was more than just fun, more than just making up dances. We were actually making a difference.”

During her junior year Brit applied to serve on the executive board, taking a job as the entertainment director where she was in charge of implementing and overseeing 18 hours worth of programming. “It was a pretty big responsibility. It’s not a job where you end up enjoying the marathon much. It’s more about running around like crazy to organize events and prepare for the next activities. That year, Purdue University Dance Marathon (PUDM) raised $303,000.

During her senior year, Brit was serving on the quad, Dance Marathon’s top tier of leadership. “That year we set really lofty goals for ourselves. We were gunning for half a million dollars.” At this stage, Dance Marathon wasn’t just social, it was personal. “I know it’s so cheesy and so cliché, but I love Ghandi’s quote ‘Be the change you wish to see in the world.’ Dance Marathon gave me the opportunity to literally take a stand in something. I was part of 300 other programs raising money for the same cause. I was part of something so much bigger than I was. I was making an impact locally and building relationships with the families we were serving. It’s the community that’s helped me find my place in this world. It’s become a party of me. I believe so much in what we do.”

At the event that year PUDM beat their mark and raised $528,000, the highest total in PUDM’s history. Zac Johnson, Dance Marathon’s Midwestern director made an appearance that night. “At that point I didn’t even realize there was a team of people advising the Dance Marathon program nationally. He came and spoke and my parents told me I should have his job.” When Dance Marathon ends, most participants pack it in for a day or two and sleep, giving their bodies a chance to recover. Instead of sleeping, Brit updated her resume and cover letter and sent it in to Zac. “I told him that Dance Marathon taught me to dream big, that even though I wasn’t the President of PUDM, I believed in dance marathon more than anything, and I would love to have a shot at the position.” There was a position open but the posting had closed two days prior. “Two days later I got an email from Zac thanking me for staying up and getting my application ready. Even though I was late, I was moving on to the next round.”Brit flew to Salt Lake City for the interview, the headquarters of the Children’s Miracle Network. After waiting a few days she received her response. She was hired.

A POWERFUL GENERATION

Millenials make a difference

Brit manages the East region which stretches from Maine to South Carolina, in addition to Indiana. As a manager she works with network hospitals to partner with universities who are setting up programs of their own. She also advises already established programs. “We challenge all of our programs to grow at least 20% every year. Part of my job is working with programs to create long term strategic goals in order to create that growth. I work with them to create a business plan from year to year. I also lead leadership retreats.”

For Brit, one of the most rewarding parts of the job is seeing college kids give back. In many ways millennials get a bad rap. In the media, older generations paint them as lazy, incompetent, and narcissistic. Dance Marathon stands in stark contrast to those claims. “Dance Marathon demonstrates that the millennials are a generation of fighters. They are changing the world for the better. They are changing it to be one we are going to be so proud to live in.” Indiana University and Purdue represent two of the largest programs in the country. This year, Indiana University raised the largest total ever accumulated by Dance Marathon, $3.6 million, up $600,000 from the year before. Likewise, Purdue University cracked the $1 million total for the first time this year. Around the country, Dance Marathons raised $62 million for the kids in 2014. “Every dance marathon organization is independently run by college students. These are students that are involved in so many other things in addition to their studies, but think about it. What major non-profit or corporation is able to experience this kind of consistent success and growth with yearly leadership turnover? Millennials really are incredible.”

The national organization sees the value in Dance Marathon as well. In total, the Children’s Miracle network saw $330 million in donations last year, including those it got from Dance Marathon. By 2020, it’s looking to hit $1 billion. “For the Childen’s Miracle Network, Dance Marathon brings in the most donors compared to all of our outreach initiatives. There is a lot of potential in young people to help us achieve that growth.”

A LEGACY OF GIVING BACK

Unexpected Dreams

Growing up, camp provided Brit with a firm foundation in faith. As a college student, camp provided the necessary opportunity to slow down and gain perspective on a world that was spinning out of control. “I’m so blessed in my life right now. I have to pinch myself. It’s because of that opportunity to come back and work at camp. I know it sounds cheesy, but I wouldn’t be doing this if it wasn’t for camp. That’s the pivotal role that camp played. I knew I didn’t have to be on TV to have a successful career. I could give back to others, be philanthropic, and I could make an impact that way. I attribute that to camp.”

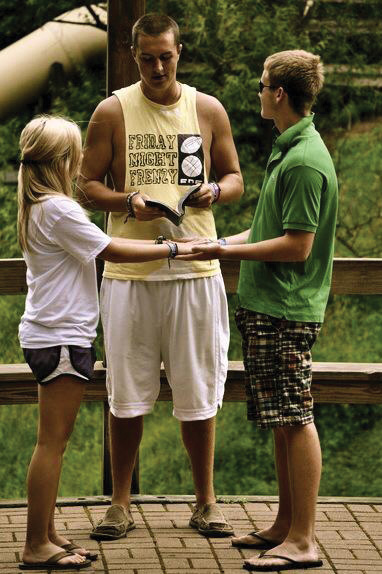

In addition, Brit and Brian are getting married. “It makes sense that the place where you feel the most yourself is the place where you’ll find your perfect match. Getting to know him where faith is the foundation, and seeing how he puts other people second, and seeing how he cares for a group of campers is getting to see the real side of a person. Camp really is the place where the real side comes out. I got to see every side of Brian through that summer.”

Brit’s back in Los Angeles now, a much different woman from her first go around as a freshman at USC. She’s planning her wedding while traveling the country in support of Dance Marathon. “My priorities are different now. Brian is doing what he loves in his dream job as an imagineer for Disney. We’re both living the dream even though it’s an entirely different dream than what first brought me out here. I wanted to make a name for myself. Now I want to build a life. We’re both giving back in order to support things we love. We’re getting involved in a church, meeting other transplants and people in similar life situations as us. This is exactly where I’m meant to be.”

This story was originally published in the winter of 2014.