God’s people left. It didn’t happen all of the sudden. It was more like drops falling from a leaky faucet; one after the other, until one day the congregation just wasn’t big enough anymore. Some blamed the steel mills. Others blamed migration from the South in a time when racial tension still sizzled with vicious heat. Either way the last few sermons washed over the deaf ears of empty pews and in 1975 the church doors closed forever.

“What happens when God’s people leave?” Joey Mayfield commands from the front of the bus. There’s a particular urgency in his voice, a soft-spoken fire; understated, but hardened. He fires off statistics with a machine gun spray. 90% child poverty rate. 50% graduation rate. 80% of black children raised in single homes. The bus rolls past the gray buildings enveloped by the gray sky in Downtown Gary when the ruins of City United Methodist Church come into view.

The limestone bell tower cranes over Sixth Avenue, casting hard shadows against 40 years of abandon. Sunlight streams through broken stained glass windows while weeds take up residence next to the towering piles of ruin. Walls washed in the aerosol spray of graffiti artists stand in silent testament to the radical change that has transformed Gary from the economic engine of Northwest Indiana to a graveyard of modernity.

The staff files off the bus, eyes wide. Cameras and phones find their way out of bags and coat pockets. A buzzy excitement permeates as the group streaks in different directions to explore the various nooks and crannies. Even after 40 years of neglect, the church is magnificently beautiful. It’s unconventional. It’s dirty. It’s dangerous. But it’s oh so gorgeous.

I suppose that’s the trick. Conversations about Gary seem to carry a certain odor, an unpleasantness that makes you wrinkle your nose just slightly and silently thank God that you don’t live there. There’s a brokenness; an assumption that with a screwdriver and the right handyman, the situation can be fixed like replacing batteries in an old smoke detector, but if even our young Bob the Builders can operate a simple screwdriver, why is the situation still so dire?

Joey Mayfield sees it. He sees the beauty, and the life, and the vibrancy, and most importantly, the potential of Gary to transform us. Sure it’s different. Sure it’s unconventional. Sure there are issues, but transformation is a two way street. The people may have left, and the church may have closed, but God is still present and active in transforming Northwest, IN. Sometimes all it takes is a conversation with a soft-spoken servant to learn how to see it.

Growing up

Joey Mayfield grew up just seven miles down the road from Camp Tecumseh. At five years of age, his mother signed him up for Day Camp, but homesickness got the better of him. He attended school with the children of camp families, and came back to camp for Outdoor Education in 6th grade.

Growing up he learned about Jesus at Flora Presbyterian church where his parents attended Sunday services. They did devotions daily and prayed together regularly. As he got older, his interest in faith waned as the youthful desire for popularity took hold, but at 17, he started reading the Bible before school. Prompted by nothing in particular, he would spend his mornings watching Sports Center and reading the Bible. After a year, he had finished the whole thing. ”Over that time period the things I was living for were not the things God wanted for me. As you read through Acts and learn about the early church, you realize that the life they are living and the things they are living for is way better than the things I was living for. I did my best to live for God as best as a high schooler can.”

At 18, his life changed when he attended a 25 day mission trip in South Africa. Three hours south of Johannesburg, he worked in the poorest part of the country. Unemployment hung at an abysmal 88%, and over 25% of the town’s population had HIV. “We’d go out in small groups, door to door telling people about the church up on the hill.”

The South Africa experience was so powerful that he came close to dropping out of his Purdue program to go back. The summer after his freshmen year of college, he returned to Tecumseh as a resident camp counselor. He worked in the Blazer unit, before coming back the next summer as the Warrior coordinator. His favorite campers were the most difficult campers: kids from bad parts of town with no positive role models.

In December of 2007 he graduated from Purdue with his heart set on missions work, but God had other plans. “God closed every single door. Slammed them right in my face. I was so frustrated with God. I had given up on my MBA program and graduated early so I could go do His work. I didn’t know what was going on.”

In the spring of 2008, Tom Elliott reached out and asked Joey to work outdoor education. “OE was huge. It took me to the next level. I’m quiet and reserved. Some people describe me as intense. Camp taught me to loosen up. In OE you have to do it all yourself. By the end, I had teachers asking me if I had a theater degree.”

After OE ended, Joey got married and took a job as an analyst at Arcelor Mittal Steel in East Chicago. “For 2 ½ years I worked as a spreadsheet jockey, but during that time God changed my heart about the people in the workplace. It taught me the benefit of having people in all sectors of society.”

He hadn’t been whisked off to a foreign country. He wasn’t preaching the gospel to indigenous tribes in third world countries, but the seeds of service were being sewn. He was falling in love with Northwest, Indiana and sometimes the most important work that needs doing needs done in our own backyards.

“Do they shoot there?”

The call to spend time with kids never really leaves a camp counselor. A few years shuffling spreadsheets for a steel company and Joey found himself at the Boys and Girls Club in East Chicago playing dodge ball with 40 kids on his way home from work. “They had never met a white dude they could get close to. Most didn’t know there was life outside of East Chicago.” Upon learning that Joey wasn’t from East Chicago, a 6-year-old girl asked, “Do they shoot there?” “I had to think for a minute. Is she talking about hunting? She told me she heard gunshots a lot. She is six years old and the first thing she asks me is, ‘do they shoot there?’ I learned that she was sleeping in the closet whenever her mom had to work her second job because she was scared.”

Sometimes exposing the cyclical nature of the problems experienced in these communities just takes a few conversations with kids. “These kids have never left their community. They don’t even know where Crown Point is which is just 20 minutes away. They’ve never seen anything different. They are living to the best definition of health their community provides. The best thing they see is somebody with a nice Oldsmobile with 20” rims. They have a big TV and lots of friends. That’s the ideal definition of health in that community. How can we get mad at a kid for trying to get the best of what their community offers? They are conditioned by where they are. They don’t have the same opportunities.”

How do you transform a community in decline? How do you break the cycle of poverty and make sure it stays broken? It starts first with identifying the problems. It starts with getting to know your neighbors.

Know your neighbor

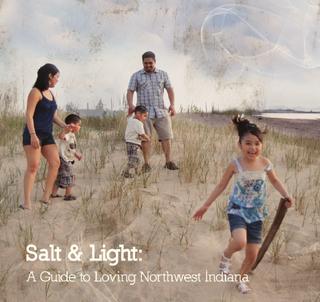

In the late 2000s an idea was formed; a book that would answer one simple question. How can we help our neighbors if we don’t know our neighbors? From the simple question, the Salt and Light project was born. The brainchild of Joey’s co-editor Jason Topp, Salt and Light started as a penance. “Our church, and others like us, made City Methodist what it is today. We took the love, peace, and hope of Christ, along with the jobs, income, and entrepreneurial spirit and moved south.” There was a disconnect between what was happening North of IN-30 and what was happening south. Salt and Light would bridge the gap. It would unite the communities of Northwest Indiana by providing essential information to ensure that communities were getting the help they needed. It would be a book that could be read, and shared and quoted. It would go out to churches and local leaders and become a reference point for conversation. The project had to start with data acquisition. Joey, using his skills as an analyst went to work.

The job involved digging through mountains of data on everything ranging from graduation rates to divorce rates; hunger, gangs, economic development; and other important indicators. It involved interviewing key stakeholders, pastors, politicians, focus groups, and other important community leaders. The content wasn’t just written by Joey and Jason. Guest editors with a stake in particular issues and the power to operate the machinery necessary for change would pen editorials and articles on the issues. “The project gave us credibility to be at the table. We could show people that we knew what was going on in the region. We could show that we wanted to be out there.”

After a year, Jason moved on. Joey left his job at Arcelor Mittel Steel and joined Bethel church as the global and local missions director where he was put in charge of the Salt and Light project. From photography to graphic design, Joey saw the book all the way through to print and distribution.

While the book has tremendous potential to make an impact, reviews ranged from excitment to cynicism. “Some people are totally jazzed about the book. They quote it to people and use it with people. Some people just roll their eyes. They’ve seen it before. They see me with this nice shiny book, and the think I’m trying to be this savior white guy.”

Drive bys and white messiahs

Gary has a Drive By problem, and not in the way you think. Back pocket solutions to ‘fix’ Gary abound amongst those familiar with the situation. Spend money on this and cut money on that. Volunteer here and spend time there. “A lot of people have a God complex. They show up unannounced ready to fix everything and take over.” As the Salt and Light editor he frequently takes phone calls from groups and individuals looking for quick fix projects. “Gary is where white people go to assuage their guilt. They do this project, check it off the list, and feel better about themselves.”

In part, that quick fix mentality breeds cynicism. People come and go with regularity but don’t stick around. There is no continuity. Ideas don’t have time to germinate because nobody gives them the time and patience necessary to make lasting, meaningful change. For those with roots in Gary, the checklist do-gooders wash away in a sea of transient faces. “What the people who really need help need is a relationship, not a lesson.” As Joey sees it, poverty is the result of broken relationships, the absence of shalom. Building those relationships takes time. It requires the ability to see beauty in desolation and despair. It requires empathy and trust, and the ability to deal with disappointment. Only through that slow relationship building process can exposure and education happen.

There’s something magical about those relationships. They aren’t one sided. The transformative effects are felt just as powerfully by the one initiating the relationship. “We need each other. This isn’t just about making Gary better. It’s about all of us becoming better. We in Crown Point can learn so much from Gary: steadfastness, happiness in the midst of desolation and need, and how to deal with tragedy.”

Ultimately, the goal of Salt and Light is to develop longstanding, mutually beneficial relationships between all parties in Northwest, Indiana. “We want people to start seeing that this is our whole community. If one part of that community isn’t doing as well, we need to step up and do a better job.”

He’s starting small: monthly prayer meetings with pastors and community leaders from all over Northwest Indiana, and frequent checkups with local boards and committees to uncover new needs and information. It’s going to take time, but Joey’s patient. He’s in it for the long haul.