On late August nights the conversations between counselors on the back porch are tied together by a dominant narrative thread. “What’s next?” On the surface, it’s hectic class schedules and extracurricular activities. Some may be studying abroad, starting an internship, or even beginning a new career.

But that’s not the interesting part of the question. The real question is much harder to answer. “What comes next now that we’ve had this experience? How do we reconcile the difference between where our hearts are now compared to where they were when we began? How do I use what I’ve been given?”

For Lydia DeMoss, the answer to that question was a long time coming. Having grown up the daughter of a full-time Camp Tecumseh staff member, she had been immersed in the lessons of Tecumseh her entire life. Her quest to answer that question took her around the world to a refugee Camp in Northern Iraq.

While Camp Tecumseh is an integral part of so many childhoods, very few kids have the opportunity to grow up here. Lydia is one of the few.

Matt DeMoss, Lydia’s father, worked full time at Camp Tecumseh as the office manager. Together with her six siblings, she grew up in the big white house at the bottom of the River Village entrance hill where she spent her days wandering around in the pine forest, playing soccer and frisbee in main field with her siblings, and befriending the Camp staff.

Each summer brought hundreds of campers and counselors which always meant new friends and new experiences. But it was during the slower months when Lydia really discovered Camp’s deep commitment to the principles it espouses. “The Camp staff were always such good role models because they automatically think kids are valuable and they treat you like you’re valuable. They’ll spend time with you, even when they aren’t babysitting you, and talk to you. They all have so many of those good qualities that you end up looking up to them.”

Like all of the DeMoss children, Lydia was homeschooled where she developed tight bonds with her family and learned how to get along along with a small group of people over long periods of time. “Our relationships are really diverse. We’re so close because we know so much about each other, and we really have this thick foundation of values that we always come back to. We care about the same things. We care about each other. And we can always come back to that even as we diverge in interests or activities.”

As a camper, Lydia was immersed in the lessons of the I’m Third motto, internalizing the values of service to others, stewardship of what we’re given, and relationships based in love and trust. It’s at Camp she learned how to be generous with her time and put her talents to work.

However, it took awhile for her to develop the confidence to pursue what she cared about. “When I was younger, my personality tended towards copying people to fit in with them. That was true of me for a really long time. It wasn’t until my second year as an Overnight Camp counselor where I figured out I just wanted to be my weird self, and I didn’t care if other people went along with it. And Camp provided the perfect environment to do that.”

She developed a passion for using humor and silliness as a motivator in her work with kids. She developed a passion for building authentic, God-centered relationships where people can talk about real life, and real struggles. Most importantly she developed a passion for a theology that goes somewhere, that has real ramifications for people in their daily actions, that requires real tangible actions on part of believers.

During her senior year at Purdue University where she studied English education, she faced the prospect, for the first time in her life, of not coming back to Camp. “I felt this huge void and I was weirdly emotional. My friend told me my Camp withdrawal sounded like a breakup.”

As Lydia reflected on her gifts and talents and on her desires for her life, she decided she wanted to serve in an area of really high need, where she could combine her skills and her passion for social justice and advocacy. She focused her attention on refugees, but refugee communities can be difficult to access. That’s when her friend introduced her to ELIC.

“My friend was studying linguistics and Arabic, and she had been talking about wanting to do a study abroad program. Then, she started talking about this opportunity she had to teach in a refugee community in Iraq with an organization called ELIC. As she was describing it, I realized that it was checking all of my boxes.”

It didn’t take Lydia long. She checked out the website, filled out her application, and committed. This is where she wanted to go. This is what she wanted to do.

Founded in 1981, ELIC works with governments and institutions to provide education and leadership in countries throughout Southwest Asia, Northern Africa, and the Middle East. Through short-term and long-term assignments, ELIC works with college students like Lydia as well as adults and gives them opportunities to teach and build relationships in communities of high need.

Lydia stopped first in Istanbul, where new ELIC recruits destined for countries around the world gathered for orientation. “It was great to be around people who had the same kind of passions I had after being around so many people who thought I was crazy for wanting to do this. It made me feel like this is where I was supposed to be.”

In addition to sessions on curriculum training and safety, many of the lessons from her training mirrored the lessons she had learned at Camp over 20 years: communication, conflict management, and leadership. After four days, she boarded a plane for Iraq.

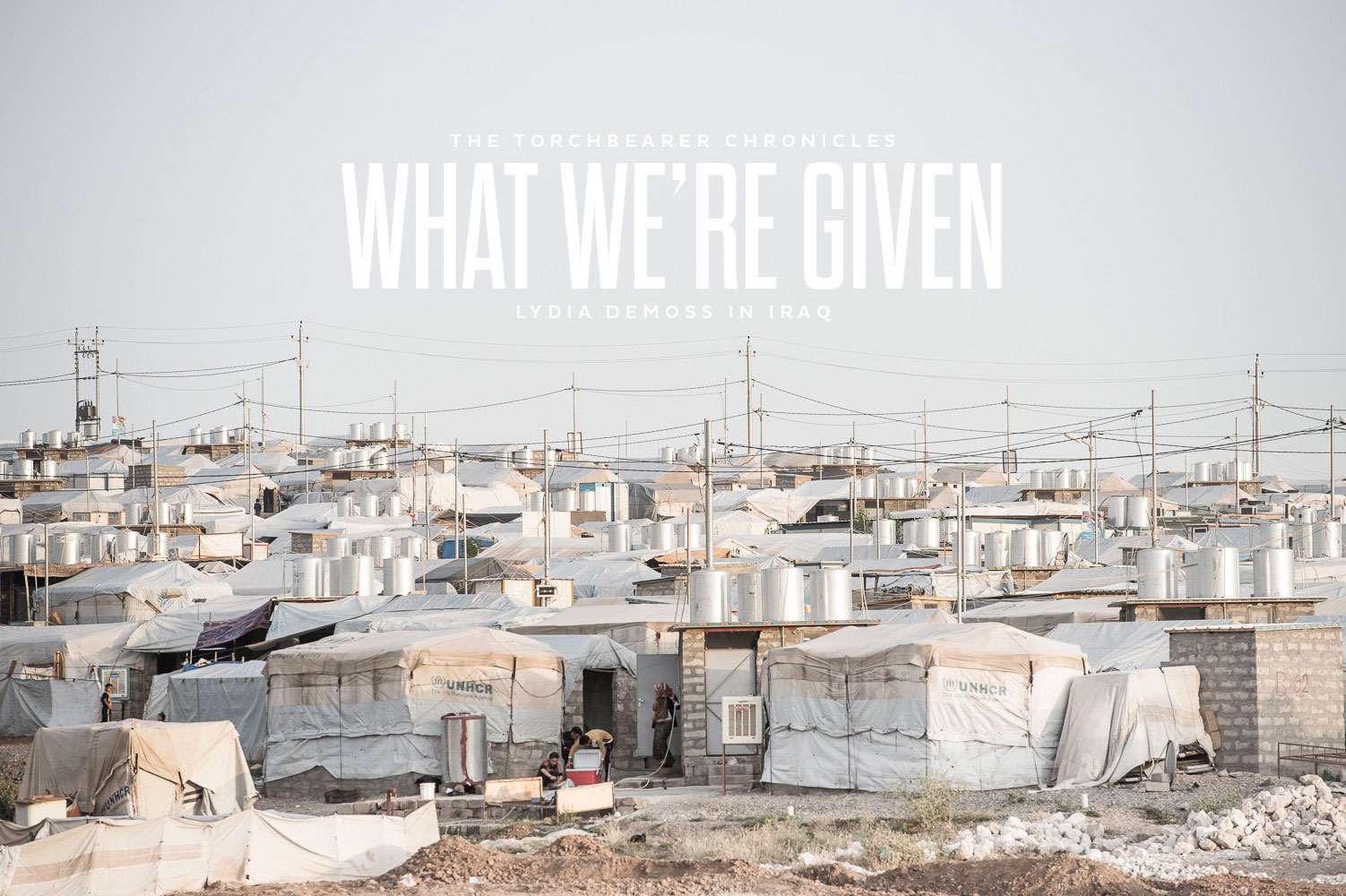

Lydia had been assigned to teach English in the Khanke refugee Camp outside of Dohuk in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq. With roughly 250,000 people Dohuk featured many modern amenities: a university, shopping malls, hotels, and restaurants and most of the population understood at least a little English.

Every morning, Lydia would gather in the lobby of their hotel with the 25 teachers on her team and make the 40 minute trek to Khanke to teach.

In the summer of 2014, ISIS forces pushed through Iraq, displacing over 3 million people desperate to escape the atrocities that had befallen their countrymen. The Khanke Camp houses over 18,000 of these refugees, over half of them children. Members of the Yazidi, the camp’s residents share a loose political alignment with the Kurdish people through a shared antagonism towards ISIS.

Composed of row after row of tents, the camp bustles with activity. Kids, goats, and chickens wander freely. Residents sell fruit, vegetables, and trinkets along the side of the road. Members of NGOs bustle about fixing and making. People fend off boredom with soccer balls and conversation. It’s clear that residents of Khanke Camp have been here for a long time.

Despite the frustration of the situation, and the terrible atrocities that led to it, Lydia always detected an undercurrent of hope. “These were just people who were trying to move forward with their lives and figure out what comes next.”

At all times Lydia balanced her desire to build real relationships while giving people space. “We were told not to push too much. These people were used to western journalists coming in all the time. They were tired of people asking them to recount all the horrible things that had happened to them.”

Every morning, Lydia and her fellow teachers would enter the Camp and head to the building housing their classrooms.

Consisting of all girls, not because of segregation—there were many mixed gender classrooms—but just by luck, Lydia’s students ranged in age from 11-16. “They started out so quiet. They weren’t really themselves. They were always talking in whispers.” It took Lydia and her co-teacher three days to transform the classroom into a silly, raucous adventure. “After three days they were yelling and talking and laughing so much. We had to start making them raise their hands just to speak.”

The girls always demonstrated an eagerness to learn. English is incredibly difficult, and no matter how much they didn’t understand, they always wanted to be there. Most of the kids had at least some experience inside a classroom, and many had a rudimentary understanding of English. “You’d start a lesson on colors, and they would know 6 out of 10. Some knew their names but couldn’t keep them straight. Some could fudge the ABCs.”

At recess, all the boys would rush to the basketball court to play games and arm wrestle and run around, while many of the girls gathered in small groups to sing, dance, and play hand clapping games. “It was like the stuff you do before lunch during summer camp.”

While the kids acted like a boisterous group of campers, occasionally the students would write about their experiences when answering simple writing prompts, making the reality of war much more tangible. “It was tough. It made all these big horrible things that had happened seem real. We had a face and a story on a piece of paper that helped us connect to what had happened.”

After a very short month, Lydia’s time in the classroom was up, and it was time to go home. “I didn’t want to go yet. I felt like I had just started to figure out the culture. I had just started building these relationships. I was just starting to get to know these girls and their personalities. And I was just starting to help them across the language barrier. I was an emotional wreck because I realized it was all coming to an end. What was going to happen to the work I had been doing?”

One of the most difficult parts of an experience like this is coming home and trying to explain it to other people. How do you answer, “How was your trip?” in 15 seconds over and over and over again?

Sitting across the table at Greyhouse Coffee, Lydia reflects on her experience and the lessons she’s learned.

While short-term trips have some impact, nothing can compare to planting yourself in a community and committing over the long-term. “I’m a big believer in the impact of relationships over a long period of time. That’s how I want to spend my life —committed to places for the long haul.”

ELIC doesn’t just place short-term teachers. They have long-term assignments as well, and the difference is notable. “There’s something different about the teachers who had been there for two or three years. They knew people. They knew the different customs, and languages, and even where to get bacon. They were part of the community.”

We have a tendency to trivialize the complexity of issues and events. “Something as iconic as the Arab world’s treatment of women is so much more complex than we think from a distance. You have to be close to actually see that. Because it’s impossible to be close to everything, we need to reevaluate our stances on the things we aren’t close to and admit that we can’t be right or wrong until we have more information. We have to invite uncertainty.”

Lydia’s experience provided an opportunity to use her gifts and talents to serve God, and in the process, she learned a more subtle and powerful truth: God leads us down a path, and asks us to learn along the way so we can better serve him. “The trip was an example of what God’s been teaching me. He showed me how the body of Christ cares for itself. He showed me how people step up for each other in times of need and use their gifts in unexpected ways in service of others.” It’s all just another lesson on a long path. Just another gift. Something else we’ve been given to use in the service of others.